Cantillon Effect

The Cantillon Effect is the most important economic concept you’ve never heard of. Here, we break down what it is and why you should care.

The Cantillon Effect is the most important economic concept you’ve never heard of. In this article, we give a breakdown of what it is and why you should care.

Origins of the Cantillon Effect

Richard Cantillon was an Irish-French economist and philosopher born in the 1680s. He achieved success as a banker—which he attributed to the formidable connections made through his family and employer. At a young age, he had learned of the impact of proximity to power.

Around 1730, Cantillon wrote a paper—Essay on the Nature of Commerce in General—which is considered a foundational work in the study of the political economy. It was widely circulated in manuscript form, though it was not published until 1755, well after his death.

In the paper, Cantillon posited that the early recipients of new money entering an economy will benefit more significantly than those it trickles down to. In other words, the "flow path" of the new money matters!

In 18th-century terms, those closest to the King—the source of money/power—benefitted first when new money entered the economy. Broadly, Cantillon observed that new money creates distributional effects based on where it enters the system. The Cantillon Effect was thus born.

Illustrating the Cantillon Effect

Let's use a very simple story to illustrate Cantillon's central point:

Imagine you live in a tiny, enclosed island society. One morning, you wake up to find a package on your doorstep. You open it up and see that it has $1 million in it. Great! But now what? No one else knows you received this package.

You now secretly have $1 million new dollars. Naturally, you start spending it (and maybe investing it) quickly. Prices are still low because no one knows these new dollars exist yet! Your standard of living improves rapidly. You buy yourself the nicest house, the most beautiful clothes, and a bunch of land—and still have some money left over.

But now, people see and feel this new money flowing through the system. Prices begin to rise as supply has yet to "catch up" to the new demand. It takes time.

So, while the money improved your life, it didn’t benefit others in the same way. The sellers of the goods—who received your cash—now face rising prices when they consume. Same with the workers who produced the goods. There were distributional effects—the flow path mattered!

This is—quite obviously—an ultra-simplified example, but it gets at the essence of the problem that Cantillon highlighted. Proximity to the source of new money is relevant—the entry point and flow path have distributional consequences.

Why you should care today

Well, with the "money printing" activity of central banks globally and an expanding wealth inequality problem, mentions of the Cantillon Effect have accelerated. It's a useful lens through which to evaluate the monetary and fiscal response to COVID—and its potential impact.

Here’s a very simple view of what we see:

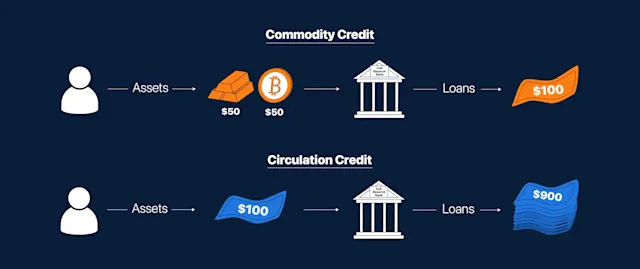

The Federal Reserve's escalating asset purchases have an injection point at the top. Direct stimulus checks—on the other hand—have an injection point at the bottom. The former was much larger $$$ than the latter.

The asset purchases—and rock-bottom interest rates, among other things—generally benefit asset owners (the wealthy). Those with a significant portion of their net worth in equities, real estate, or similar assets have benefited significantly during Covid.

Wage earners—who received some degree of support but did not benefit in the same way from asset appreciation—are getting the short end of the stick. Inflation—particularly across food and energy prices—will impact lower-paid workers who hold onto cash and cannot afford to own assets / or equities.